The idea that our art institutions need reorienting has been especially pressing this spring. Recent controversies, such as the Hannah Black-initiated call for the removal and burning of Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket (2016), in the Whitney Biennial,1 the protest by four Dakota tribes and their supporters against Sam Durant’s Scaffold (2012), which resulted in the work’s removal from the Walker Art Center’s sculpture garden,2 and the protests around the traveling exhibition of Carl Andre’s retrospective,3 all highlight the view that museums need to expand their programs to present more works that address intersectional issues with sensitivity to subjects such as racial subjugation, gender disparities, class differences, and (post)colonial histories. It appears equally pressing that sensitivity to those subjects must be woven into the curatorial practices of the museum. Indeed, in all of the above controversies, the museums and the curators who work there were called out and called upon as much as the artists involved. In the case of the Walker, the museum’s executive director, Olga Viso, stated publicly, “There’s no question that the Walker’s process in placing this structure in the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden was flawed…”4 It is in the context of more rigorous expectations for contemporary institutions that I consider Machine Project: The Platinum Collection (Live by Special Request), the documentation of Machine Project’s 2015 exhibition at The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, in Saratoga Springs, New York. The Platinum Collection makes clear Machine’s goal of affecting the inner workings of museum culture, one invitation at a time.

Machine Project: The Platinum Collection (Live by Special Request), installation view, The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY, September 19, 2015–January 3, 2016. Courtesy of The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College. Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber.

Machine Project is a Los Angeles-based arts organization created by Mark Allen that serves as an umbrella for individual and collective projects by artists and non-artists alike. Working out of the same storefront space for 15 years, Machine Project is a “feral institution,” presenting installations, theatrical productions, pedagogical workshops, tours of its oft re-configured interior, and a multiplicity/superabundance of other offerings.5 The storefront also serves as a headquarters for administering off-site projects, including large-scale programming realized at and with other venues. Los Angeles is home to several projects founded by artists desiring to produce extra-institutional spaces for criticality and innovation. Mark Bradford’s Art + Practice, Noah Davis’s The Underground Museum, and Sara Velas’s Velaslavasay Panorama come to mind as endeavors that thrive outside of established museums, galleries, and universities.6 While Art + Practice, for example, works within an urban neighborhood as part of an expanded field of art, Machine often works within more conventional art world parameters. Its innovation is in the practice of inserting itself (back) into established institutions. The museum-based projects allow Machine to concoct scenarios on a scale not allowed by its modest space. They also function as a trickle-up experience for the hosting institution—a training, of sorts, in how to facilitate artworks that are participatory, ephemeral, and/or durational. Most importantly, that training often involves publicly processing the experience after the fact, an exercise museums don’t typically undertake.

Machine Project: The Platinum Collection (Live by Special Request), installation view, The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY, September 19, 2015– January 3, 2016. Courtesy of The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College.

Two early and ambitious projects were especially formative for Machine’s training credentials: a festival-style, one-day residency at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), in 2008, and a year-long inhabitation of the Hammer Museum, from 2010 to 2011. The LACMA occupation consisted of at least 53 happenings that took place over 10 hours.7 The Hammer residency involved a greater number of more substantive projects—75 of them, with 300 artists participating—which was a quantity heavy enough to tax the museum’s infrastructure and personnel. The stress incurred by the hosting institution while enacting such extensive programming over so many months was registered publicly in the 182-page report produced after the fact by the museum and Machine. In an interview between Allen and Allison Agsten, the Hammer’s former Curator of Public Engagement, Agsten revealed: “One thing, last year, that became difficult internally was the number of programs we were producing. It became really clear for this year that we needed to consider ways we could moderate flow. We had the period from August to September—do you remember?—it was madness: we had Soundings: Bells at the Hammer, we had Houseplant Vacation, and then we had Brody’s Level5 over Labor Day weekend. By the end of that, people were beat.”8

At other junctures in the report, Agsten refers to “friction” and “conflict” between the two organizations, but ultimately credits the relationship as allowing the museum to “make a quantum leap forward in a way that I can’t imagine we could have otherwise.” Specifically, she mentions that, after working with Machine, she became sensitized to “the power that intimacy can have.” She also comments, “Sort[ing] through so much was really good, accelerated learning. It showed us what our limits were, what we could handle here, what we couldn’t handle here.” The Museum’s ability to utilize its interstitial spaces for programming also improved during Machine’s tenure there.9

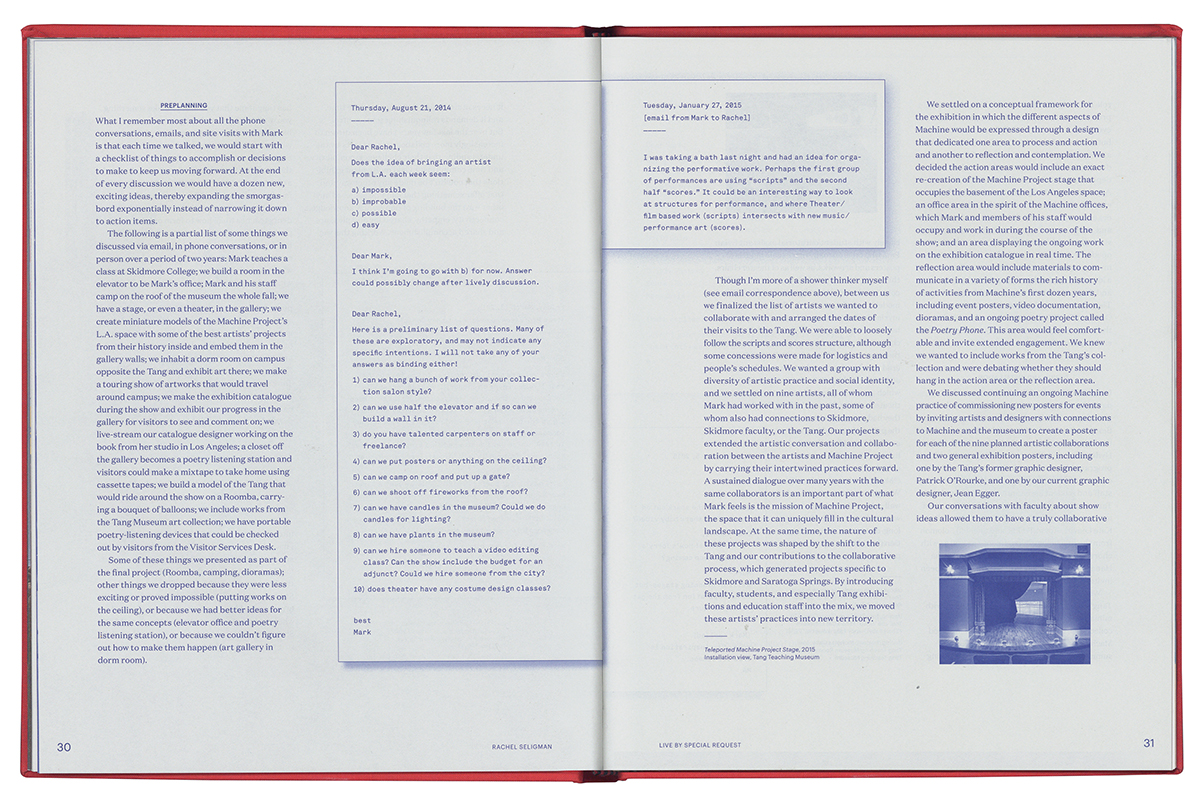

Machine Project: The Platinum Collection (Live by Special Request) (Munich, London, and New York: The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College and DelMonico Books•Prestel, 2017), page 30. Exhibition catalogue. Email correspondence between Mark Allen and the museum’s curator Rachel Seligman. Courtesy of The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore Collge and Content Object.

Since those initial residencies, Machine has been invited to put other institutions through their paces, including the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota; Colgate University and the town of Hamilton, New York; and Southern Exposure, San Francisco. In Charlotte Cotton’s essay “Field Guide to Machine Project,” in The Platinum Collection, she describes this period in Machine’s history as “Collaborations with major cultural institutions across the country to reimagine forms of public engagement and accessibility.”10

Indeed, Machine has received more of these invitations than it can accept, and at one point tried working with institutions in a straight consulting capacity, off the exhibition record. The strategy of the organization Working Artists and the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.) comes to mind. W.A.G.E. has undertaken a very direct approach to addressing how institutions compensate artists, by offering annual certification to institutions that meet its few requirements. Started by a group of artists, it has remained, since its inception, in the realm of bureaucracy and regulatory bodies.11 Its methodology rejects the idea that artists should have to negotiate with an institution in isolation, instead taking the preemptive route of advocacy. Machine’s approach, even in the experimental consultancy, lies within a Venn diagram that comprises collective organization, creative production, and institutional advocacy. At the same time that it is staging multiple artists’ projects, it’s also modeling a different kind of curatorial method—one with heavy emphasis on subsequent processing of the experience by Machine and the hosting organization, in publication form.

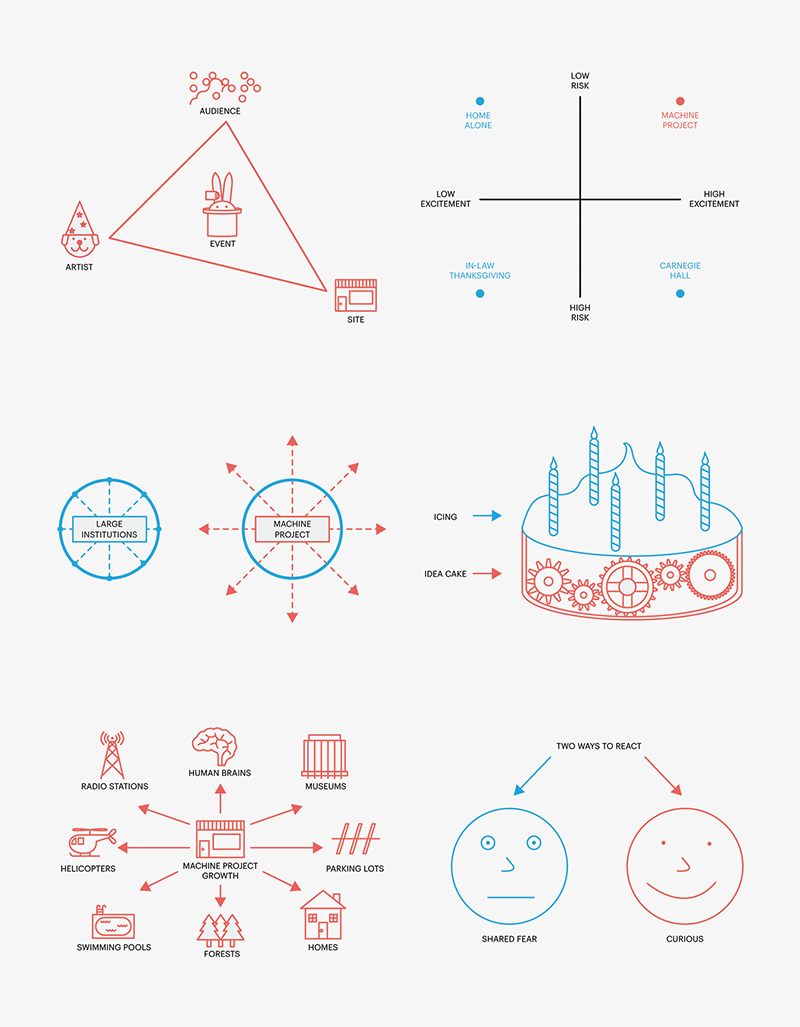

Machine Project, explanatory diagrams, 2014. Reproduced in Machine Project: The Platinum Collection (Live by Special Request) (Munich, London, and New York: The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College and DelMonico Books•Prestel, 20 7), page 64. Courtesy of The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College.

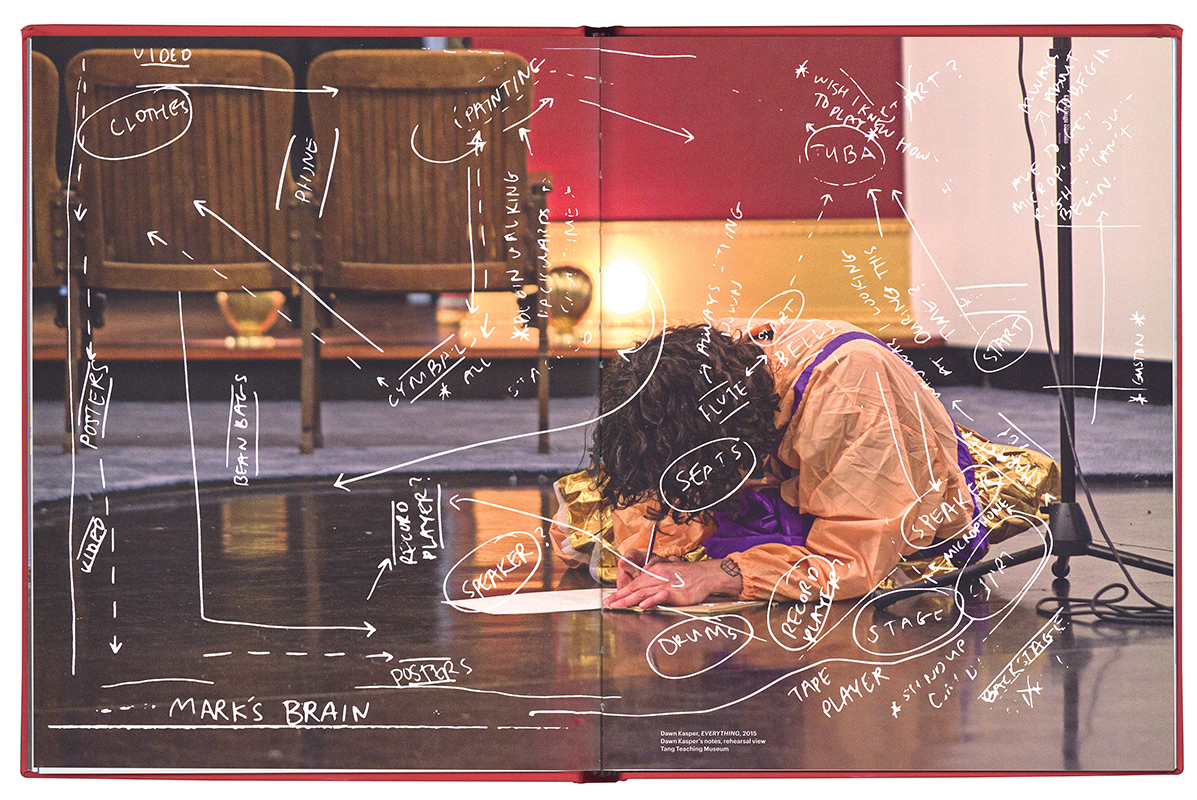

Machine’s recent exhibition and residency at the Tang Museum, for which it produced the book Machine Project: The Platinum Collection, was intended to be a retrospective of sorts. A primary feature of the physical exhibition was a proscenium theater, with a replica of the stage in Machine’s Los Angeles storefront and chairs sourced from a local Waldorf School. The exhibition also included a Machine administrative office; a poetry phone; a beanbagged lounging area beneath a multitude of the posters created for events from Machine’s history; and a to-scale model of the Tang Museum mounted on a Roomba, which roamed through the space. Throughout the run of the show, artists—many of whom have worked extensively with Machine in the past—arrived on campus to enact workshops (Dawn Kasper), performances (Asher Hartman), wanderings (Joshua Beckman), sonic massages (Carmina Escobar), perception exercises (Krystal Krunch), and so on. Most of the artists engaged students, staff, and faculty with varying degrees of intensity. The Tang exhibition had all the hallmarks of a Machine endeavor: multiple artists presenting multiple non-object-based, participatory experiences; an effort to expose the process of arts administration; references back to its storefront in Los Angeles; engagement with locals and the locale; a humorous self-consciousness about the exhibition-making process; and a certain buoyancy of affect. Indeed, the Tang show and accompanying monograph document how Machine Project has honed its methodology into something that can travel outside of its home city into different-sized institutions.

The focus on pedagogy is fitting for a show at the Tang, a teaching museum at Skidmore College with a remarkably large number of faculty who engage with its programming each academic year.12 In the world of social practice art, this museum represents an institution well oriented to its surrounding community, serving it as well as learning from it. The Tang’s methodology and allocation of resources facilitate durational, socially engaged work, as well as ample opportunities for feedback and evaluation after the fact. Over the years, Machine has given an unusual emphasis to reflection and analysis of its endeavors, and here the two organizations’ practices dovetail in a book that is both ambitious and illuminating.13

Especially apparent in The Platinum Collection is the sheer quantity of programming that is central to Machine’s strategy. The book contains the list “Every Machine Event 2003–2015,” with reproductions of every poster produced for those events. Less long, but still ample, is the list of “Every Poetry Project Ever” produced by Machine, as remembered by writer Joshua Beckman and Mark Allen. The book’s introduction, by Ian Berry, is a compilation of 45 quotes from sources including artists, a baseball player, and Nike ad copy.14 The abundance factor is also in full force in Allen’s essay, “Hello, have you been here before,” an annotated version of an audio guide to Machine’s Los Angeles storefront space which revisits many past projects and moments big and small. Chatty and intimate annotations take up a majority of the visual space, and offer a wealth of background information on Machine’s hallmarked methodology. Modeling a casual enthusiasm and performatively sincere pursuit of wonder, the writing itself feels like a lesson in affect: in the footnote about the power of the reveal, Allen writes, “The lecture that becomes a meal that becomes a legal deposition that becomes a dance performance that becomes an art installation that becomes a lecture that becomes your parents’ anniversary party. A good reveal is the definition of underpromising and overdelivering!”15 Allen’s essay also articulates Machine’s insistence on transparency about its process and intent. Many of the footnotes seem pointedly aimed at educating institutions, reorienting curators, and encouraging individuals to create their own feral organizations. There are notes about why Machine remains a small organization, despite the “metastasizing logic of the art world;” details about the practice of “giving prompts to artists as a curatorial approach;” tips on how to start an art space; ideas about how to work across disciplines (“What does a geologist have to say about a marble statue?”); an explanation of why “game face is super important” for organizers; a discussion about event documentation; a discussion about event promotion; and an eight-item list of what has “helped [Machine] make better, more satisfying work with the public.”16

Asher Hartman and Cliff Hengst, Mr. Akita, 2015. Cliff Hengst performs at The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY, September 27, 2015. Courtesy of The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College. Photo: Ian Byers-Gamber.

Multiple transcriptions of emails between Machine and the Tang provide further examples of how an exhibition can be made and administered. We get glimpses at the beginning stages of the relationship, when Allen deftly and discreetly probes to determine the Tang’s desired scale and available budget, then middle-stage correspondence that documents the piling on of ideas for what could be included in the exhibition, and finally some after-the-fact missives about de-installation practicalities that reveal an affectionate dynamic between the two organizations. These inclusions provide insight into stages of arts administration that are not usually accessible.

Artists’ projects always have the potential to destabilize entrenched practices and herald paradigm shifts. But the institutional re-orientation that they produce might only become apparent in a future shift in programming, a decision to work—or not to work—with an artist who has a certain kind of practice, or a staff member’s spontaneous disclosure in a panel discussion. For instance, in 1971, Hans Haacke’s solo exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York was canceled by the museum after its board characterized his work Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real-Time Social System as of May 1, 1971 (1971), which chronicles the fraudulent dealings of two New York City slumlords, as “muckraking,” rather than art.17 This was an early instance of a major museum refusing to allow the work of an established artist to directly implicate its inner workings, choosing instead to censor the work. In most cases, including Haacke’s, the intricacies of the negotiations around challenging works and an acknowledgement of the growing pains they can produce typically remain restricted to private conversation and correspondence. Unique to Machine Project’s endeavor is the way it prompts institutions to reflect publicly on their challenges and shortcomings.

The fact that curators and arts administrators have elected to learn new ways of working via Machine-led exercises, such as the Tang exhibition, is especially significant at this point in time. It is in sharp contrast to the reorientation-through-trauma model that Durant’s Scaffold induced, where the Walker’s response and subsequent outreach about the problematic artwork occurred at the last minute, amidst turbulent protests, threats, and intense online debate. It is different again from the straight certification model offered by W.A.G.E. Machine’s consistent emphasis on public documentation and meta-consciousness around the administration of the work (publishing emails, exposing paths not taken, engaging in group analysis after the fact, explicating the already annotated practice) offers a model for how organizations can be more transparent in their times of reorientation. As a collective that draws on the work of many artists, Machine is uniquely situated to enact the artist-as-administrator or artist-as-consultant role within an institution. The pains of growing are diffused, or maybe even deflected, by Machine’s ultimate role as artist-as-curator. With this one move, Machine situates itself to meet (other) curators and administrators on a different playing field than a singular artist might. The loose group of practitioners that constitutes Machine for any one of its residencies or exhibitions provides a framework for the artists that helps ameliorate the disparity of scale between an individual artist and a museum.

Dawn Kasper rehearses EVERYTHING (2015) at The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY, October 24, 2015. Reproduced with Kasper’s notes in Machine Project: The Platinum Collection (Live by Special Request) (Munich, London, and New York: The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College and DelMonico Books•Prestel, 2017), pages 114–15. Courtesy of The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College and Content Object.

Machine models this strategy of solidarity while offering a plethora of programming to the institution. The prevailing metric for socially engaged art practice, when it is taken up by conventional institutions, is still “bums in seats,” where quantity counts, with funders looking at the number of viewers (and artists) served. Machine measures up well in this calculation, giving museums what they want—sometimes too much. Its friendly approach allows institutions to feel comfortable entering into the after-the-fact accounting of the administrative process.

One wonders what would it look like if there were a book-length documentation from the recent crisis involving Durant’s sculpture at the Walker, which is unfolding as I write? It might include candid contributions from the curator(s), the artist, independent curators with relationships to the local Native American communities, and the Dakota Elders, who could have been consulted before the artwork was made in 2012 for three European exhibitions or, at the very least, before it was installed this year in Minneapolis.

We are finally at a moment when institutions must consciously elect to undertake a re-orientation process with regards to issues of race, gender, and economics. The transparency and reflection extensively documented in The Platinum Collection offer a model for how museums can make these changes accessible and available for circulation. Perhaps then the process of learning how to be truly post-colonial, inclusive, and humane can be more widely understood and taken up within the art world. What were institutions thinking, we ask? It can be shown.

Anna Mayer is a Los Angeles-based artist who works sculpturally in her solo practice and socially as CamLab, her 11-year collaboration with Jemima Wyman. She has been the Assistant Director of the Institute For Figuring since 2009.